Bob paused in the shadow of the alley behind the inn, waiting for the fat man with the fatter purse to exit the bar and stumble by. Across the river the Knarlytooth mountains rose to 8000 feet, glacially carved into spectacular spires of granite and dolomite.

Seriously? Why the hell would Bob pause to think about the geology of the mountains across the water? Answer: he wouldn’t! So we don’t get to, either. This POV is called “third person limited” and is the most common these days. TPL means we the readers are passengers in the POV character’s mind, limited to what he notices. In “third person omniscient” we would not be limited to his knowledge, but that POV is fairly rare these days.

The only way we get to learn about the mountains is if the mountains were somehow relevant to Bob in that scene–like, say, the moon was about to rise from behind them and reveal his position–then he’s worried about them, and so we get to see them. It might go like this:

Bob paused in the shadow of the alley behind the inn, waiting for the fat man with the fatter purse to exit the bar and stumble by. He glanced over his shoulder at the jagged peaks of the Knarleytooth mountains, the broken spires backlit with the rising moon. Two minutes, maybe less, he judged, before the moon cleared the lowest pass and illuminated the alley. He stifled a curse and turned his attention back to the inn. If his mark didn’t show soon, he’d have to give it up.

The rule here is this: filter your world details through the point-of-view character. We the readers only get to see/experience what the POV character would notice.

Michael Swanwick does this masterfully in Stations of the Tide. Check out this passage from the first chapter. In it, the protagonist, known only as “the bureaucrat,” is of on a space ship, skimming over the surface of distant planet on a mission for his department.

“Smell the air,” Korda’s surrogate said.

The bureaucrat sniffed… “Could use a cleansing, I suppose.”

“You have no romance in your soul.” The surrogate leaned against the windowsill, straight-armed, looking like a sentimental skeleton. the flickering image of Korda’s face reflected palely in the glass. “I’d give anything to be down here in your place.”

That’s all you get for the explanation of what the hell a surrogate is, or who Korda is, because we are experiencing this passage through the bureaucrat’s POV, and to him a surrogate’s as common as a cordless phone to us, and he knows Korda well. The bureaucrat will neither pause to reflect on the marvel of surrogate technology for our benefit, nor on his relationship with Korda, both of which he takes for granted; we are therefore left to piece it all together through his perspective as the story unfolds.

Their dialogue stretches over four pages, and it’s pretty easy to figure out that Korda is his boss, but we only get one small clue on each page as to what a surrogate is. Here are the clues, excerpted from the action of the dialogue.

…”Korda moved away from the window, bent to pick up an empty candy dish, and glanced at its underside. There was a fussy nervousness to his motions strange to one who had actually met him. Korda in person was heavy and lethargic. Surrogation seemed to bring out a submerged persona, an overfastidious little man normally kept drowned in flesh.”

…”The surrogate reopened the writing desk, removed a television set, and switched it on.”

…”They shook hands, and Korda’s face vanished from the surrogate. On automatic, the device returned itself to storage.”

In the end, I’ve pieced something together about this wonderful piece of worldbuilding known as the surrogate, and what I come up with is pretty damned cool. But Swanwick never explains it to us. He sticks religiously to what his POV would notice about the situation.

In the end, this sort of writing relies on me to do some of the lifting, and I dig that. It’s a big reason I buy everything he writes. There aren’t a lot of writers who do it as well as he does, and if I ever do it half as well I’ll be pretty damned proud of it.

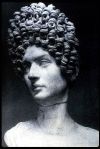

Collars of any era are likely to have a high absurdity factor—think of the Virgin Queen, or John Travolta’s character in Saturday Night Fever. Shoes are also common offenders, and hairstyles.

Collars of any era are likely to have a high absurdity factor—think of the Virgin Queen, or John Travolta’s character in Saturday Night Fever. Shoes are also common offenders, and hairstyles.

noblewoman’s hairstyle from the decade she died, which appeared to be a mass of tight curls piled in what can be only be described as a cross between a beehive with a radar dish.

noblewoman’s hairstyle from the decade she died, which appeared to be a mass of tight curls piled in what can be only be described as a cross between a beehive with a radar dish.