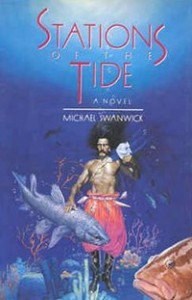

I take a lot of inspiration and instruction from Michael Swanwick’s Stations of the Tide. The book is full of fantastic inventions that he limns with only in the lightest brushstrokes. I referred to his “surrogate” technology in the post on “Filtering Setting Through Character POV”. In this post I want to share two other examples: one of the “jug” dwellings in the riverbanks on Miranda; the other of a drug/toxin derived from  a bacterium or micro organism.

a bacterium or micro organism.

First, the jugs.

This far east, the farmland was too rich to squander, and save for the plantation buildings, most dwellings hugged the river. Unpainted clapboard houses teetered precariously on the lip of a high earth bluff. Halfway down to the water, a walk had been cut into the earth and planked over to serve a warren of jugs and storerooms dug into the banks itself (176).

He doesn’t tell us what a jug is. He just refers to them, because his POV character, the bureaucrat, knows what they are, and would not pay them any particular notice, so we don’ t get to either. It isn’t until eight paragraphs later when the bureaucrat is inside a cafe that we learn.

…In a niche by the table a television was showing a documentary on the firing of the jugs. There was antique footage of workers sealing up the new-dug clay. Narrow openings were left at the bottom of what would be the doors, and to the top rear of the tunnels. Then the wood packed inside was fired. Pillars of smoke rose up like the ghosts of trees and became a forest whose canopy blotted out the sun. The show had been playing over and over ever since its original broadcast on one of the government channels. Nobody noticed it any more.

“The heat required to glaze the walls was—” The bureaucrat reached over and changed the channel (176-177).

What I love about this is that he trusts me as a reader enough to let me hang for eight paragraphs before I find out what it means. Yes, I had to read the first description twice, because I didn’t know what a “jug” was, but there was enough context for me to assume it was some kind of dug-out dwelling space, and that was enough for me to go on till I got some more description.

He could have explained it right away: …a warren of storerooms and jugs, ceramic-walled rooms carved from the clay and baked in place with massive internal bonfires or something, but that would have bogged down the action at hand.

In the end, was this neat invention relevant to the action at hand? No. in that regard it’s a throwaway detail. But in terms of sustaining the protagonist’s sense of alien landscape and people, a kind of stranger-in-a-strange land vulnerability and therefore tension—it was.

Here’s how he introduces the drug/toxin.

Pouffe sat opposite the two of them, his back to the land. His face was puffy and unhealthy in the window light. His eyes were two dim stars, unblinking…

Gregorian walked over to Pouffe, and crouched. He cut a long sliver of flesh from the old shopkeeper’s forehead. It bled hardly at all. The flesh was faintly luminous, not with the bright light of Undine’s iridobacteria but with a softer, greenish quality. It glowed in the magician’s fingers, lit up the inside of his mouth, and disappeared. He chewed noisily.

“The feverdancers are at their peak now. Ten minutes earlier and they’d still be infectious. An hour later and their toxins will begin to break down.’ He spat out the sliver into his palm, and cut it in two with his knife. “Here.” He held one half to the bureaucrat’s lips. “Take. Eat.”

The bureaucrat turned away in disgust.

“Eat!” The flesh had no strong smell; or else the woodsmoke drowned it out…He obeyed (232).

(The bureaucrat then experiences hallucinations, out-of-body experience, into-Gregorian’s memory experience, like the pensieve in Harry Potter, and that’s all we get.) He could have had Gregorian explain what the toxins do, and how they work—he could have had the bureaucrat muse on what he knew of feverdancers, but he doesn’t. We are left to assume all that from these few clues, and it is enough.

Light brush strokes, carefully limited by the POV character’s POV.