Rough Guide to Fantasy Land is the This is Spinal Tap of Fantasy.

It’s also a humorous guidebook of cliches to avoid when writing fantasy. Here’s a fun review of it from a funny reviewer, Barb Taub.

Weirder than Fiction

Building Believable (and Fantastic!) Fantasy Worlds

Reality is often truly stranger than anything you could make up, so it pays to research.

Take this picture from a late 17th century fashion mag displayed in the Rijks Museum, Amsterdam. Look close.

Look how hard these guys are working! That hair! Those stockings! Those accessories! They look like 80s glam rockers!

The Inredibles

Turns out, there was a name for this Captain Jack Sparrow style of dress back then. Here is what the Rijks Musuem had to say about them in their Fashion Magazines exhibit: They were called, “The Incredibles.” Not kidding.

So This was Actually Satire of the High Fashions of the Rich!

Still, I am not sure they succeeded in making it more ridiculous than the actual fashions. How could they? Here is one of the men they mocked, also from a fashion mag of the time:

Dude. You’re wearing pink and white candy-cane-striped tails with yellow pantaloons. Nailed it.

Extremities of Female High Fashion

I wish I had more pictures of ridiculous wealthy men’s attire from the time, but most of the extreme examples are of women’s fashion.

Like these insane hairstyles for women.

The Ship one is my favorite:

Here is the Timeless Message of High Fashion:

1) Since no one could possibly do work in such attire, I am clearly wealthy.

2) Since the time it takes to design and execute such confections of hair/clothing makes it impossible to do any actual work during the day, I am clearly wealthy.

3) Since the cost of my fashion–not just in time but in money–is astronomical, I am clearly wealthy.

Building This Principle Into Fantasy A World

A good illustration of this in fantasy is in Martin’s A Game of Thrones (the books, anyway) where the fashion of the noble women of the slave city of Meereen is a dress that is essentially a mummy wrap from neck to ankles, making it impossible for the women to walk in anything but tiny little steps. Clearly, those women are NOT doing any work!

Here’s a dress from modern day high fashion that might have been from Meereen:

I apologize I don’t know where this image came from originally, or I would cite it. I found it via google on a Pinterest page. Anna D made a comment connecting it to Daenerys in Meereen.

Finally, a Note on the Timelessness of Junk Grabbing

Okay, pant-sagging may not have been around in the old days, but the Incredibles did, apparently, grab junk. They were straight up Gs.

I asked Luke Shea, freelance animator/artist, to make a trailer for THE JACK OF SOULS. Due to my inexperience as an art director, what we ended up with is more of a YA primer to the world of the Jack, but whatever it is, it’s really fun, and Luke is amazing. (That’s also his voice as the narrator!)

Check it out here:

I recently attended an author reading of a humorous supernatural fiction novel that shall remain nameless. After hearing several chapters from the beginning and middle, I found my self thinking, “The main character’s voice is hilarious, but the dude is a douche, a parasite who makes a living ruining other people’s lives; he never shows remorse for it, never justifies it, nor in fact does he ever give us the sense there is need for justification.

It brought up a question I have as a writer that is still not fully resolved. It is based on the assumption that a protagonist must be a sympathetic character. I used to think this meant the reader has to like the main character, or identify with her/him. A wise writer friend of mine suggested that we don’t have to like them, per se–nor particularly identify with them–but we do have to be able to sympathize with them, at least in some small way.

Breaking Bad

I suppose that’s why the protagonist of Breaking Bad was able to keep people with him for x seasons; he was despicable in many ways–more and more as the seasons passed–but viewers sympathized with his troubles and miseries. Likable? No. Sympathetic? Quite.

If I Laugh, Do I Sympathize?

Back to the supernatural novel. The only thing this protagonist had going was that he was funny as hell. His snarky voice made me chuckle. But sympathize? I don’t know.I suppose the roots of the word sympathy mean literally, “to feel with.” I guess if this unlikable protagonist is making jokes and I’m laughing, I’m sympathizing with him–literally “feeling humor with him.”

But that reasoning makes me dizzy and I still don’t feel I sympathized with him.

Not Funny Enough

So I bought the book based on the chuckles I got from the reading, but only read halfway through before I put it down. NOTE TO SELF: Turns out, funny isn’t enough to form that emotional attachment with a protagonist I need to want to spend a lot of time with them.

To be fair, the author seems to have cherry picked some of the funniest passages in the book to read to us, so maybe I lost sympathy simply because the rest just wasn’t funny enough. I was there for the cherry passages of hilarity, then…the ick showed through.

Until I meet another such character who is much funnier, I won’t know the answer.

Corollary Observation: The Comic Get-Out-of-Jail-Free-Card

A funny narrator can get away with much that would spoil a story with an ordinary narrator. for example, info dumps of exposition cause readers to skim ahead, or sigh and doggedly push through in hopes such dumps won’t come often.But I’ve read info-dumps that were so funny I didn’t care at all. My friend Craig has that knack. I could read his exposition all day.

So I remain undecided as to whether an unsympathetic protagonist can be similarly redeemed by being very, very funny.

If you know examples of characters that fit that bill, let me know! I’d love to hear your thoughts below.

My kids are finally old enough to watch Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring! Naturally, I excavated the extended version ( I ‘d carefully sheltered it from the family DVD bin that accelerates the laws of entropy), and we had a family movie night.

Watching it, however, I relived my initial disappointment with its world building at the level of sound. Specifically, I found myself rolling my eyes when the Black Riders showed up. Why? Because the sound engineers had an opportunity to imply worlds of weirdness with the sounds emanating from the ringwraiths, but instead used what has become the clip art of scary monster sounds — the high-pitched squeal of pigs.

Clip-Audio

It’s everywhere. Think about it. The sound of velociraptors in Jurassic Park? Pig screams. The six-armed invaders from Cowboys and Aliens? Pig screams. The weird proto-alien-squid monster aborted from the heroine of Prometheus? Pig screams! The mile-high Kaiju of Pacific Rim? Freaking pig screams! It doesn’t seem to matter if the creature is as big as the Empire State Building or as small as a terrier, it’s going sound like a psycho pig.

It’s as if the last time anyone put any effort into world building on the level of sound was when William Friedkin recorded the screams of pigs herded for slaughter for use in The Exorcist. Back then, this sound was original and brilliant and effective. Now it is the clip-audio of monster sounds. It’s as if Friedkin’s feat of sound imagination was so awe-inspiring that even Peter Jackson could find nothing more appropriate for the ghosts of the ancient kings of Middle Earth than the sound of shrieking swine. (To be clear, I don’t know if he actually recorded pigs, per se–chances are a synthesizer could create it from scratch–but the two are virtually indistinguishable.)

(To be clear, I don’t know if he actually recorded pigs, per se–chances are a synthesizer could create it from scratch–but the two are virtually indistinguishable.)

I wish I could dub Teletubby tracks over it; I swear that would be scarier. (Or imagine a velociraptor making Teletubby sounds… Gives me a shiver!)

Visual Trumps Audio

I have to assume that Hollywood is so “visually” focused that it undervalues the value of sound in world building. But when I refer to sound as an element of world building, I think of it as a visual component. For example, when Legolas draws his funky elvish blade, and it goes schwing! in a perfect C major, I visualize clean, honed, shining steel. When the orc draw’s its blade it better not sound the same. For that we’ll need a gritty, metal-on metal scrape, so we visualize a rusted, blood-caked machete of a blade, which implies as much of orc culture as the schwing does of elves. (Wait…Okay, you know what I mean.) My point is this: sound choice can economically imply layers of visual detail, just as word choice can in prose.

What if the Audio had been as Brilliant as the Visuals?

Consider the layers of eerieness one could imply about the bizarre half-life of the ringwraiths if their sounds had instead been alluring or musical, like mournful pipe organs? Or flatly metallic? Or distant whispers like urgent messages heard through a long pipe? Or if they’d been utterly soundless/sound devouring as in Joss Whedon’s wonderful Buffy episode, “Hush?”

But no one does that any more. Even Cameron and his visually resplendent bioluminescent Avatar forests used the pig-scream clip-audio for the calls of his four-eyed flying mounts. (Look out! Flying pigs!) The aliens in Whedon’s Avengers were apparently from a pig planet, too. Those aliens, along with the invaders in Aliens and Cowboys, are obviously of highly intelligent, technologically advanced species, yet they had no discernible language or patterned vocalizations other than pig screams. And while I’m thinking of it, the advanced race of squid-headed aliens in Independence Day? Pig screams.

Bright Spots in Hollywood Monster Audio?

1) District 9’s aliens! Huzzah!

2) … ( Anyone…? Anyone…?)

Turn it Upside Down

Instead of striving for something “scary” sounding (sounds that are harsh, threatening, violent), I humbly suggest we do the opposite. Try giving the monster a voice that is lovely, or even ridiculous. Ever hear the voice of America’s favorite bad ass raptor, the American Bald Eagle? It’s not the haunting Kii! Kii! dubbed in for its appearance in Hollywood films or Colbert’s title sequence (that cool sound is actually the sound of a red-tailed hawk). The bald eagle’s voice is the fruity piping of a seagull on crack: “Keetle- KEETLE-keetle! Keetle-KEETLE-keetle!”

Hard not to giggle, the first time you hear it. But give that sound to a monster as it tugs the guts out of someone’s family dog, and the discordance would be quite chilling.

In less than a week we get to see The Desolation of Smaug and find out what the spiders in Mirkwood sound like! …Anyone want to make a guess?

Please let it be Teletubbies.

Tolkein’s Legacy

The reason you don’t see lots of new Tolkeinesque stories of halflings and dwarves and elves in the book stores is that those things have been done. Most people want something new. It isn’t that dwarves and elves and halfllings can’t be used in stories any more, it’s just that if you use them, you probably need to re-invent them in some unexpected–even iconoclastic–way in order to make them fresh again for the reader.

One could argue that the genre of urban fantasy is largely the result of just such a need for newness and rethinking. Black Blade Blues comes to mind, with its investment-banker dragons–what a wonderful re-imagining that is! (Who are the hoarders of gold today–the symbols of greed–if not the Gordon Geckos?)

I recently took my kids to the wonderful Crest Cinema to see the animated film, Rise of the Guardians, in which the artists reimagined the all too familiar figures of Santa and his elves. How did they reinvent them?

Santa became a burly, tattooed Russian with a rolling Russian accent, a huge rough laugh, and the words Naughty and Nice tattooed on his massive forearms.

His “elves” were replaced with teams of huge and hairy yeti, who were responsible for all the toy making (as well as any fistfights that needed staffing).

Okay, there were elves present–the standard cliche elves with tiny bodies, cute faces and pointy ears and hats–who laid about (drunk, in my memory) and idle, as a kind of window dressing, but even that was a reinvention of elves.

As a result, the old tropes were again fresh and entertaining, and in some cases can even cause us to question our assumptions about the familiar (do Russians have a different idea of Santa?).

The excerpt below is also from Mary Sisson’s Trust (see previous posting).

This scene actually precedes the one in the previous post (sorry–out of order, I know). it is actual moment of first contact when Daring Attack sees Trang and his marines before they have the universal translator present.

Since the universal translator is not yet in the scene, language is not the thing being held up in the “mirror” for us to examine. Instead, Daring Attack focuses on our physical form, which, to him is very strange as his species is an eye-less quadruped with no “head,” to speak of. His first guess is that the humans might be Mechanical Aliens (i.e. remotely operated drones operated by a third species of alien that can’t move around in air).

Excerpt One

He was closer to the Mechanical Aliens now. He could hear them.

“Oupa oupa oupa!” said one.

“Oupa oupa,” replied another.

The aliens were mostly sticking near their vehicle, folding something up. But one of them began walking closer to where Daring Attack was. As it came closer, Daring Attack realized with a start that it had only two legs.

A Two-legged Alien, not a Mechanical Alien, he thought. Unless the Mechanical Aliens also have only two legs.

No, he decided, as he watched the alien tip forward, lurch a leg underneath itself to keep itself from falling, and then repeat the process. It was a miracle the thing didn’t just flop over and wriggle about helplessly on the ground. This two-legged thing is too bizarre to have been ignored.

(And then later when they find the translator and can talk to him)

The Two-legged Aliens said they were happy to see him, which made Daring Attack wonder if he had overreacted when they surrounded him—maybe they had just been curious. In any case, after a few minutes of conversation with the diplomat, the four in the brush stepped back out into the clearing.

Not that talking to them was any less unnerving. Close up, Daring Attack could see that the aliens had this ball-shaped appendage that was connected to the rest of their body by only a slender stalk, which looked like it could be chopped through in an instant. This appendage never stopped wobbling—it would wobble when they talked, it would wobble when they were silent, and when they walked, the appendage wobbled atop their wobbly, lurching bodies.

It made Daring Attack dizzy.

God I love that. Those last four of five lines had me laughing out loud.

Some of the best spec-fic holds up a mirror in such a way that we see aspects of our species/culture anew. Often this is accomplished by showing first contact. Ursula Leguin’s Left Hand of Darkness comes to mind, with its human diplomat arriving at a planet of hermaphrodites; also Larry Niven’s Ringworld, with its humans, puppeteers, and kzinti.

The First-contact Mirror

I recently found a hilarious first-contact mirror in Mary Sisson’s novel Trust (sequel to Trang), which follows the human diplomat Phillipe Trang as he interacts with five or six different species of alien.

In these scenes, inter-species communication is made possible by a Universal Translator device, which struggles to decode the expletives of the human space marines assigned to protect Trang. Since the POV in the scene is that of the alien, the results are hilarious and thought provoking.

Excerpt from Trust

(Setting: Trang and his marines meet the alien (named Daring Attack) near their crash site on a wild and remote part of an alien planet as a giant T-rex-like thing referred to as a “Giant Mankiller” approaches through the jungle. The dialogue starts with the marine nick-named Princess).

“I cannot see it,” said Noble Person, who was holding a machine to its face.

“Of course not—if it was that close, we’d be dead,” said Daring Attack.

“What distance—” Noble Person stopped.

“His units for measuring length—” said the diplomat.

“I am knowledgeable of that fact,” said Noble Person. “If the carnivore continues toward us at the rate of travel at which it is currently traveling, at what time will it reach us?”

“His units for measuring time—” said the diplomat.

“May it remain for eternity in the mythological place where the spirits of the ignoble dead reside!” said Noble Person.

“I express my regret,” said the diplomat.

“There it is,” said the alien holding the sheet.

“Sacred digestive by-product,” said Noble Person.

Daring Attack tried not to dwell on the fact that he was risking his life for people who worshipped digestive by-products. Instead, he noticed a large dark blob on the sheet.

“Mythological figure who regained life after being dead for three days and is engaged in reproductive activity, it is large,” said the other alien.

“Is that the carnivore?” asked Noble Person.

Daring Attack looked at the blob. Was that the Giant Mankiller? He couldn’t tell.

(When the marines send armed drones to attack the Giant Mankiller, the marines watch through video monitors, muttering…)

“Draw closer on, you small individual conceived in a socially inappropriate manner,” said the alien. “Draw closer and obliterate that buzzing flying insect that is engaging in reproductive activity with you.”

Has it gone insane? Daring Attack wondered.

After I was done howling with laughter, these are some of the things I found myself thinking about:

Why do humans use feces and sex in expletives? Okay, we’re primates, we like to throw poo, and now that we have words to do it with, we don’t need to get our hands dirty. I get that. But sex? Do all human cultures do that, or just puritanical Western ones? For that matter, do (puritanical) Islamic cultures do that? Do Hindis? Do the Chinese? The Japanese? Maori? Australian Aborigines? Are we all sex-and-potty mouths?

If you are fluent in these cultures, please comment and share.

The Muse of Invention

One of the best things about speculative fiction is the joy of pure invention, riffing off of patterns we see in the Nature. The florescent flora of Miranda, in Avatar, comes to mind–stunningly beautiful, inspired perhaps by some of the bio-luminescence of the sea.

(Image of flora in Avatar) (Image of florescent sea anemone)

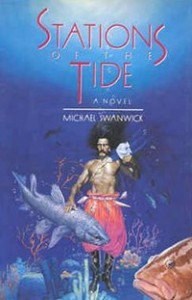

Michael Swanwick’s Stations of the Tide

Here is a passage from Stations of the Tide that I thought beautiful, inspired perhaps by the symbioses we see among sea creatures–from whales to crabs–like barnacles, remoras, and whale lice.

The orchid crabs were migrating to the sea. They scuttled across the sand road, swamping it under their numbers. Bright parasitic flowers waved gently on their armor, making the forest floor ripple under a carpet of multicolored petals, like a submarine garden seen through clear fathoms of Ocean brine.

Years ago the book was recommended to me by the leader of Seattle Writer’s Cramp, Steve Gurr, when he pointed out some arbitrary apostrophes I’d inserted into place names or secondary character names in the novel I was submitting for critique at the time. (His point about the apostrophes wasn’t that one ought not use apostrophes in imaginary place names, but that if I am not a linguist, like Tolkien was, I might consider doing that sparingly. (And yes, Jones does have a humorous entry on Apostrophes in the book.)

I read all of Tough Guide to Fantasyland and found numerous inspirations to reconsider elements of my worldbuilding which I had not before examined.

Some of My Favorite Examples

COLOR CODING: is very important in Fantasyland. Always pay close attention to the color of the CLOTHING, hair and eyes of anyone you meet. It will tell you a great deal. Complexion is also important: in many cases it will be color coded too.

1. Clothing. Black garments normally mean EVIL, but in rare cases it may mean sobriety, in which cases a white ruffled collar will be added to the ensemble. Gray and red clothing mean that the person is neutral but ending to EVIL in most cases. Any other color is GOOD, unless too many bright colors are worn at once, in which instance the person will be unreliable. Drab color means the person will take little part in the action, unless the drab is also torn or disreputable, when the person will be a loveable rogue.

2. Hair. Black hair is EVIL, particularly if combined with a corpse-white complexion. Red hair always entails magical POWERS, even if these are only latent. Brown hair has to be viewed in combination with eyes whose color are the real giveaway (see below), but generally implies niceness. Fair hair, especially if it is silver-blonde, always means goodness.

3. Eyes. Black eyes are invariably EVIL; brown eyes mean boldness and humor, but not necessarily goodness; green eyes always entail talent, usually for magic but sometimes for music; hazel eyes are rare and seen generally to imply niceness; gray eyes mean niceness and healing abilities (see HEALERS) and will be reassuring unless they look silver (silver-eyed people are likely to enchant or hypnotize you for their own ends, although they are not always EVIL); white eyes usually blind ones, are for wisdom (never ignore anything a white-eyed person says); blue eyes are always GOOD, the bluer, the more good present; and then there are violet and golden eyes. People with violet eyes are often of Royal, and, if not, always live uncomfortably interesting lives. People with golden eyes just live uncomfortably interesting lives, and are usually rather fey in the bargain. Both these types should be avoided by anyone who wishes for a quiet life. Luckily it seldom occurs to those with undesirable eye colors to disguise them with ILLUSION, and they can generally be detected very readily. Red eyes can never be disguised. They are EVIL and are surprisingly common.

4. Complexion. Corpse-white is evil, and it grades from there. Pink-faced folk are generally midway and pathetic. The best face-color is brown, preferably tanned, but it can be inborn. Other colors such as black, yellow, blue and mauve barely exist.

So, if a character is wearing green, is blue-eyes and brown-faced, you will probably be okay. CAUTION: do not apply these standards to our own world. You are likely to be disappointed.

CLOTHING: Although this varies from place to place, there are two absolute rules:

1. Apart from ROBES, no garment thicker than a SHIRT ever has sleeves.

2. No one ever wears socks.

COATS: do not exist in Fantasyland–CLOAKS being universally preferred–but TURNCOATS do.

CLOAKS: are the universal outer garb of everyone who is not a barbarian. It is hard to see why. They are open in the front and require you at most times to use one hand to hold them shut. … etc.

Amazon Link

Consider reading this aloud to like-minded geek friends.

I take a lot of inspiration and instruction from Michael Swanwick’s Stations of the Tide. The book is full of fantastic inventions that he limns with only in the lightest brushstrokes. I referred to his “surrogate” technology in the post on “Filtering Setting Through Character POV”. In this post I want to share two other examples: one of the “jug” dwellings in the riverbanks on Miranda; the other of a drug/toxin derived from  a bacterium or micro organism.

a bacterium or micro organism.

First, the jugs.

This far east, the farmland was too rich to squander, and save for the plantation buildings, most dwellings hugged the river. Unpainted clapboard houses teetered precariously on the lip of a high earth bluff. Halfway down to the water, a walk had been cut into the earth and planked over to serve a warren of jugs and storerooms dug into the banks itself (176).

He doesn’t tell us what a jug is. He just refers to them, because his POV character, the bureaucrat, knows what they are, and would not pay them any particular notice, so we don’ t get to either. It isn’t until eight paragraphs later when the bureaucrat is inside a cafe that we learn.

…In a niche by the table a television was showing a documentary on the firing of the jugs. There was antique footage of workers sealing up the new-dug clay. Narrow openings were left at the bottom of what would be the doors, and to the top rear of the tunnels. Then the wood packed inside was fired. Pillars of smoke rose up like the ghosts of trees and became a forest whose canopy blotted out the sun. The show had been playing over and over ever since its original broadcast on one of the government channels. Nobody noticed it any more.

“The heat required to glaze the walls was—” The bureaucrat reached over and changed the channel (176-177).

What I love about this is that he trusts me as a reader enough to let me hang for eight paragraphs before I find out what it means. Yes, I had to read the first description twice, because I didn’t know what a “jug” was, but there was enough context for me to assume it was some kind of dug-out dwelling space, and that was enough for me to go on till I got some more description.

He could have explained it right away: …a warren of storerooms and jugs, ceramic-walled rooms carved from the clay and baked in place with massive internal bonfires or something, but that would have bogged down the action at hand.

In the end, was this neat invention relevant to the action at hand? No. in that regard it’s a throwaway detail. But in terms of sustaining the protagonist’s sense of alien landscape and people, a kind of stranger-in-a-strange land vulnerability and therefore tension—it was.

Here’s how he introduces the drug/toxin.

Pouffe sat opposite the two of them, his back to the land. His face was puffy and unhealthy in the window light. His eyes were two dim stars, unblinking…

Gregorian walked over to Pouffe, and crouched. He cut a long sliver of flesh from the old shopkeeper’s forehead. It bled hardly at all. The flesh was faintly luminous, not with the bright light of Undine’s iridobacteria but with a softer, greenish quality. It glowed in the magician’s fingers, lit up the inside of his mouth, and disappeared. He chewed noisily.

“The feverdancers are at their peak now. Ten minutes earlier and they’d still be infectious. An hour later and their toxins will begin to break down.’ He spat out the sliver into his palm, and cut it in two with his knife. “Here.” He held one half to the bureaucrat’s lips. “Take. Eat.”

The bureaucrat turned away in disgust.

“Eat!” The flesh had no strong smell; or else the woodsmoke drowned it out…He obeyed (232).

(The bureaucrat then experiences hallucinations, out-of-body experience, into-Gregorian’s memory experience, like the pensieve in Harry Potter, and that’s all we get.) He could have had Gregorian explain what the toxins do, and how they work—he could have had the bureaucrat muse on what he knew of feverdancers, but he doesn’t. We are left to assume all that from these few clues, and it is enough.

Light brush strokes, carefully limited by the POV character’s POV.

The Sucker Punch of Speculative Fiction Novels

I think the falcon-chick affect (see preceding post for explanation of this syndrome) is why a writer’s first novel generally doesn’t have a prologue. For a falcon chick reader, the prologue is the ultimate sucker punch. It’s like saying, “Here, read this prologue, bond with the prologue protagonist, then learn in the first chapter that she died ten centuries before the main story begins.”

This may be why agents and editors don’t like to put them in a debut novelist’s first novel. Established writers can get away with using prologues, because they already have an audience that trusts them, and because they are less likely to use a prologue as an expository crutch.

Sampling a few debut novels from the last couple years seems to bear this out:

Notably, Gilman’s sequel, City of Gears, has a prologue. He proved himself.

Still, being an established author does not override my falcon-chick complex. I can think of a few established authors I put down after I bonded with a prologue character who never reappears in the novel. Saberhagen’s The Book of Swords was one. Tigana, by Guy Gabriel Kay, was another. The only exception that comes to mind is the prologue to Martin’s A Game of Thrones, where the character relationships were so gorgeously crafted that (ironically) I forgave him when they died.

Kristin Nelson’s “Agent Reads the Slushpile” Workshop

I also noticed yesterday that when Kristin Nelson held a recent “first-pages” workshop she instructs participants to send the first couple pages of their manuscript: “It needs to be the actual, opening first 2 pages of your manuscript. If you have a prologue, skip it and grab page 1 and 2 from your chapter one.” That may be a coded form of Vonnegut’s advice to “throw away the first couple pages, because that’s where you explain everything” (see earlier posting on Vonnegut’s Writing Advice).

So the message to new writers of fantasy is clear: ditch the prologue till you’ve published. Of course, I had to be told this myself. In the fist draft of my first novel I had one. And it was hard to let it go: prologues are a nice crutch for exposition, and losing it made me work harder.

When a falcon chick hatches, it bonds with its caretaker. In nature, it bonds with the parent falcons. Some falconers prefer parent-raised falcons, but others prefer hawks who have imprinted upon the falconer, so they make sure the first thing the little chick sees when it opens its eyes is the smiling falconer, food in hand.

Readers are like falcon chicks. When we open our eyes in the new world of a novel, we imprint on the first POV character we meet. I do, anyway, and many readers I know do, too: we bond with the first character we meet, and we expect the story to stick with them. If it turns out we bonded with a shill, a throwaway prologue character who never appears again in the book, or with some secondary character whose purpose was to somehow ease me into the world or plot, then I feel cheated. It makes me peevish. Often, I’ll ditch the book right there, as I did with Saberhagen’s immortal swords tome, and Guy Gabriel Kay’sTigana (I know! It’s supposed to be magnificent! I should have skipped the prologue!).

The only way I can explain my reaction to this misplaced imprinting is that the bonding state of my mind at the beginning of a novel is a vulnerable state of receptiveness and trust; it doesn’t last long, and once it’s imprinted on someone/something, it’s done. Any further imprinting is forced and artificial and therefore uncomfortable and second rate.

My Lesson? Start the Story with my Main Character

I enjoy the watching the literary gymnastics of a story featuring numerous POV characters. Some writers like George R.R. Martin in A Game of Thrones, swap POVs every chapter, and it is truly impossible to tell who the main character is. This is compounded by his willingness to kill off literally any of the twelve main characters he’s created. He’s a master. He can do that. And when he does, he bends the genre and the realm of what readers expect and can handle. Maybe someday that kind of head-hopping will be standard.

As a general rule, however, it’s still best for the rest of us to start with our main POV character in the first chapter, so readers imprint on him or her immediately. Most readers expect that, and to break custom with that can be disorienting.

I used to start one of my novels with a secondary character POV episode that I thought was a fun way to set the world and tone before the main character entered the story. Readers convinced me to move that passage to a later chapter when they were already grounded in their main character POV.

It’s also interesting to note that when a person scans the first pages of a book in a bookstore or on Amazon, part of what they are doing is assessing whether the main character is someone whose head they want to be in for the rest of the book. Having that character up front and center is part of their expectation, and part of what sells the book.

ICE

In the late 90s I lived in Charlottesville, Virginia, where I did some contract writing for the guys at Iron Crown Enterprises, the creators of the wonderful Role Master fantasy role-playing system.

At the time they were designing a game world for a new series of modules, and the game designer, John Curtis III, mentioned something that struck me as odd at the time and so it sticks with me today. After explaining to me the intricacies of the world’s cosmology–how his world and it’s peoples were created by what gods and for what purposes–he said, “but that’s just half of it. Now I have to figure out how each of those peoples think the world was created and by whom for what purpose. None of the mortals would know the real story, only nuggets of truth here and there.”

I think of that as the “Through a glass, darkly” principle in worldbuilding. Even Christianity, which claims to be the sole true religion in this world, doesn’t claim that humans are capable of full understanding of the divine in this life. Of this world and the next Saint Paul wrote, “We see now through a glass darkly, but then we shall see face to face.” Likewise the mortals of ICE’s game world were granted only a dim and muddled view of its cosmological reality.

If you go with that metaphor for your world, the people’s mythologies will be only a shadow of what is actually going on, warped by human passions and frailties and limitations.

Playing with the Glass

Those warpings can be lots of fun. They’ll show up in contradictory scriptural passages like “God is a jealous god”, “God is love,” and “Love is never jealous.” (Wait, what?) It will show up in confabulations of folklore and scripture, like some of the Jewish golem stories, and in outright imaginative superstition, like imbedding nails in the shape of a cross in the heel of your left boot to keep the devil off your trail, as Pap does in Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Making up your own versions of that is plain fun.

The Curse of Chalion

One of my favorite examples of a secondary world designed upon the “through the glass darkly” principle is Lois McMaster Bujold’s Curse of Chalion universe. The gods in that world are very present but so inscrutable as to seem arbitrary at times, remote beyond human understanding. In books like that, I feel I’m being made to examine life and spirituality from a new angle, and I value that. But just as important is the simple verisimilitude of such crafting; it resonates with the way humans experience the divine in –through a glass, darkly–and thus brings credibility to the world.

Of course, you might well decide to create a world in which the gods live in the temples among their priests, and if there is any dispute in doctrine the priests simply ask the god, who settles it definitively. (Such a world presents an entirely different set of challenges.)

Vonnegut’s Advice in Tacoma

In 1986 or so I attended a lecture given by Kurt Vonnegut at Pacific Lutheran University. It was a “Creative Writing” conference, and he was the keynote speaker. After an hour of ranting about Ronald Reagan, he paused, took a drink of water, and said, “Well, I guess I should say something about writing now, since this is an English major conference. So I’ll give you two pieces of advice. First of all, if you want to be a creative writer, don’ t be an English major. English majors learn too much taste, and once you learn to be tasteful, you can’t be creative. I was a Chemistry major.

“The other thing is this: Go ahead and write your story, then throw away the first pages, because that’s when you explain everything. And when you explain everything, no one gives a damn any more.”

Loved that guy. I could see the professors in the room forcing smiles on their rebellious faces.

Game Designer Insight

I heard a game designer describe world building in a way that is also relevant to fantasy writers. He said, “You the designer have a floodlight, but the gamer only gets a flashlight.” What he meant by that is that as the designer or writer you know the world inside out–its history, its background, its mythology and genealogies–but the gamer or reader will never experience the vast majority of that. It’s for you, the designer to know, so you can steer the story.

It’s the same basic message as the iceberg metaphor: your world’s background would make great reading for an encyclopedia fetishist, but lousy slogging for story readers.

Another Reason to be Stingy with Exposition

As it turns out, readers are as motivated by unanswered questions about your world as they are the cool things you reveal. It’s those unanswered “story questions” that keep the reader turning the pages to find out the answers.

(For more on the idea of not revealing to much to your readers, see entries below.)

Fun with Folly

Excellent spec fic writers build this absurdity into the worlds they create. Recently, I’ve noticed two wonderful examples of writers or directors who employ this understanding to great effect. The first is George R. R. Martin, whose Slave Masters in the fifth Game of Thrones book have wonderfully absurd hairstyles sculpted in shapes like bird wings or rearing animals or supplicant hands in primary colors. The women in that culture wear tokars, which are essentially a kind of fancy mummy wrap from the armpits down, making it almost impossible to walk.

Hunger Games Fashion

The other example is the designer of the costumes, hairstyles and make-up of the elite  “capitol” culture in the film adaptation of The Hunger G

“capitol” culture in the film adaptation of The Hunger G ames. Wonderful world building.

ames. Wonderful world building.

The Emperor Has Clothes, and They are Ridiculous

The wonderful absurdity of fashion is not a new phenomenon either, as witnessed by the bizarre confections of silk and wool dreamed up by renaissance tailors in Italy.  Collars of any era are likely to have a high absurdity factor—think of the Virgin Queen, or John Travolta’s character in Saturday Night Fever. Shoes are also common offenders, and hairstyles.

Collars of any era are likely to have a high absurdity factor—think of the Virgin Queen, or John Travolta’s character in Saturday Night Fever. Shoes are also common offenders, and hairstyles.

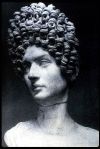

Recently I viewed a Roman tomb that captured in stone a

noblewoman’s hairstyle from the decade she died, which appeared to be a mass of tight curls piled in what can be only be described as a cross between a beehive with a radar dish.

noblewoman’s hairstyle from the decade she died, which appeared to be a mass of tight curls piled in what can be only be described as a cross between a beehive with a radar dish.

Wonderful article, by the way, in which a hair dresser plays archeologist to explain how these crazy roman hairdoos defied gravity:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/03/22/ancient-roman-hair-janet-stephens_n_2925152.html

Third Person Limited

Third person limited (TPL) is one of the most common POVs these days. TPL means we the readers are passengers in the POV character’s mind, limited to what he or she notices and thinks. If the character doesn’t see the orc creeping up behind them, the reader doesn’t get to, either.Since the character couldn’t know what the orc is thinking, the reader doesn’t get to, either.

Third Person Omniscient (or, Third Person Unlimited)

In “third person omniscient” (TPO) we would not be limited to the character’s knowledge; the narrator is omniscient, and can get inside anyone’s head. We get to find out what the stalking orc is feeling, what his victim is thinking right before the attack, and even the hidden metal armor the character is wearing under his shirt. TPO was a common POV back in the day, but these days it’s fairly rare.

Third Person Limited also Limits What a Character Would Notice

For instance, if a character has lived on a street all his or her life, she probably won’t even notice any more how it is laid out. So the reader doesn’t get to know either.

Sample

Bob paused in the shadow of the alley behind the inn, waiting for the fat man with the fatter purse to exit the bar and stumble by. Across the river the Knarlytooth mountains rose to 8000 feet, glacially carved into spectacular spires of granite and dolomite.

Seriously? Why the hell would Bob pause to think about the geology of the mountains across the water? Answer: he wouldn’t! So the reader doesn’t get to, either.

The only way we get to learn about the mountains is if the mountains were somehow relevant to Bob in that scene–like, say, the moon was about to rise from behind them and reveal his position–then he’s worried about them, and so we get to see them. It might go like this:

Bob paused in the shadow of the alley behind the inn, waiting for the fat man with the fatter purse to exit the bar and stumble by. He glanced over his shoulder at the jagged peaks of the Knarleytooth mountains, the granite spires backlit with the rising moon. Two minutes, maybe less, he judged, before the moon cleared the lowest pass and illuminated the streets. He bit off a curse and returned his attention to the inn. If his mark didn’t show soon, he’d have to give it up.

Conclusion

The rule here is this: filter your world details through the point-of-view character. Make the world details matter to the action/concerns at hand.